5

Heritage 2012: Military 05

November 9, 2012 www.plaintalk.net

Special scrapbook offers unique points of view during war years

BY TRAVIS GULBRANDSON

travis.gulbrandson@plaintalk.net

In Vermillion’s Austin Whittemore House is

an item that offers a variety of unique perspectives on World War II.

About 10 years ago, the museum acquired a

scrapbook that was put together by deceased

area resident Pearl Simonson, who clipped and

saved hundreds of items relating to the war from

the Vermillion Plain Talk and the Dakota

Republican.

“Her husband had been killed in the First

World War, and she had kept all of this material,”

said Austin Whittemore House manager Cleo

Erickson. “They didn’t have children or anything, so when they cleaned out her house, all

this stuff was in there.”

Most of the articles are dated, and many of

them feature first-hand accounts of the war

when the events were still fresh in the public’s

mind, published in the forms of interviews,

diaries and letters home.

One diary told of a member of the medical

corps who missed the attack on Pearl Harbor by

exactly one week.

“Well, it looks like it has finally happened,”

wrote Capt. Harold Hanson on Dec. 7, 1941. “We

heard the news this noon that the U.S. and Japan

are at war. Everyone here is glad we have finally

called their bluff. I only hope we are not underestimating their ability.”

Hanson wrote that immediately after receiving news of the attack, the ship’s crew began

painting the ship a dark color.

“We are in somewhat of a spot – a dangerous

one – as everyone aboard fully realizes,” Hanson

wrote.

Other service members tell of life during

training maneuvers.

“We are battling across New Mexico, and

what a place!” Lt. Jay Swisher wrote to his parents in October 1943. “I used to think that the

prairie from Vivian to Pierre was but, here you

can go for hundreds of miles and never see a

farm house.”

That same month, Lt. Hanley Heikes was

interviewed by the Republican, where he told of

serving 15 months doing engineering and supply work with the 98th bomb group in the

Middle East.

“All we could see were rocks and sand,”

Heikes said. “The wind blew constantly and was

filled with powdery red dust. We could have

clean clothes on to start the morning and by

9:30 they’d be filthy.”

Heikes added that he didn’t “know what the

soldiers would have done” without the efforts of

the Red Cross.

“The Red Cross made it possible for men to

keep going,” he said. “In our outfit the men were

given a week of medical detached service every

three months. They had to have it because of

the bad food, the heat on the desert and the

nervous strain.”

These feelings were echoed by Pvt. Sidney

Engman and Pvt. Lester L. Russell, both of

whom spent time in German POW camps.

“We didn’t smoke at all over there, but we

saved the cigarettes from our Red Cross packages to trade to the guards for bread and potatoes to keep ourselves alive,” Engman said in

July 1945. “Incidentally, you can’t say enough for

the Red Cross aid to the prisoners. It kept us

alive by giving us meat and other essentials.

“We saved out the cigarettes and tea for

barter with the guards,” he said. “A package of

tea would bring several loaves of bread.”

Engman added that a single American cigarette meant more than money in the camp –

about 60 cents per smoke.

Russell said the British Red Cross box was

“just like Christmas once a week.”

In August 1943, Russell wrote his parents

that he had “learned how to bake any or everything since I was captured,” and asked them to

send him some graham crackers.

“They would make a swell cake,” he wrote.

The diet was the worst part of camp life,

Engman said, reporting that his normal weight

of 155 dipped down to 104 at one point during

his internment.

The scrapbook offers accounts of the aftermath of battle, such as in Capt. Ralph Konegi’s

letters to his wife.

“I really saw the results of war,” he wrote

after seeing French territory that was formerly

occupied by the Germans. “At one place I went

through heavy timber-land which had been

almost stripped of the trees. The artillery fire on

it had been so severe that trees at least two feet

through were cut right off. Almost reminded me

of the results of a forest fire.”

Konegi later passed through a French city

“which was bitterly fought over by the

Americans and Germans.”

“It was so completely shelled and bombed

that the engineers had difficulty in finding the

streets,” he wrote. “Bulldozers were still being

used to clear away the rubble. Usually as we

have seen it nearly all the walls remain standing

with just a portion blasted away. But in this city

there were just small portions of the walls left

standing.”

In 1945, Lt. Don Burr wrote to his parents of

his experiences seeing the concentration camp

Dachau, which he describes as “one of the most

horrible sights I ever expect to see.”

“You’ll see it in the movies; at least what they

dare show,” Burr wrote. “Every man, woman

and child should see for themselves the crimes

committed by these German SS troops. …

“When our division captured this camp we

found the bodies of over 68,000 political prisoners that had been murdered just two or three

days before our arrival,” he wrote. “Of course,

this mass murder had been going on for

months.”

Burr’s letter does much to convey the shock

he felt on coming upon the scene.

“How any group of men and women could figure out how to kill people by the thousands I

don’t know,” he wrote.

After the war’s end, Lt. James Brick reported

on the day he spent viewing the Nuremburg trials. The day Brick attended, Hitler’s deputy

Rudolf Hess was being tried.

? SCRAPBOOK, Page 07

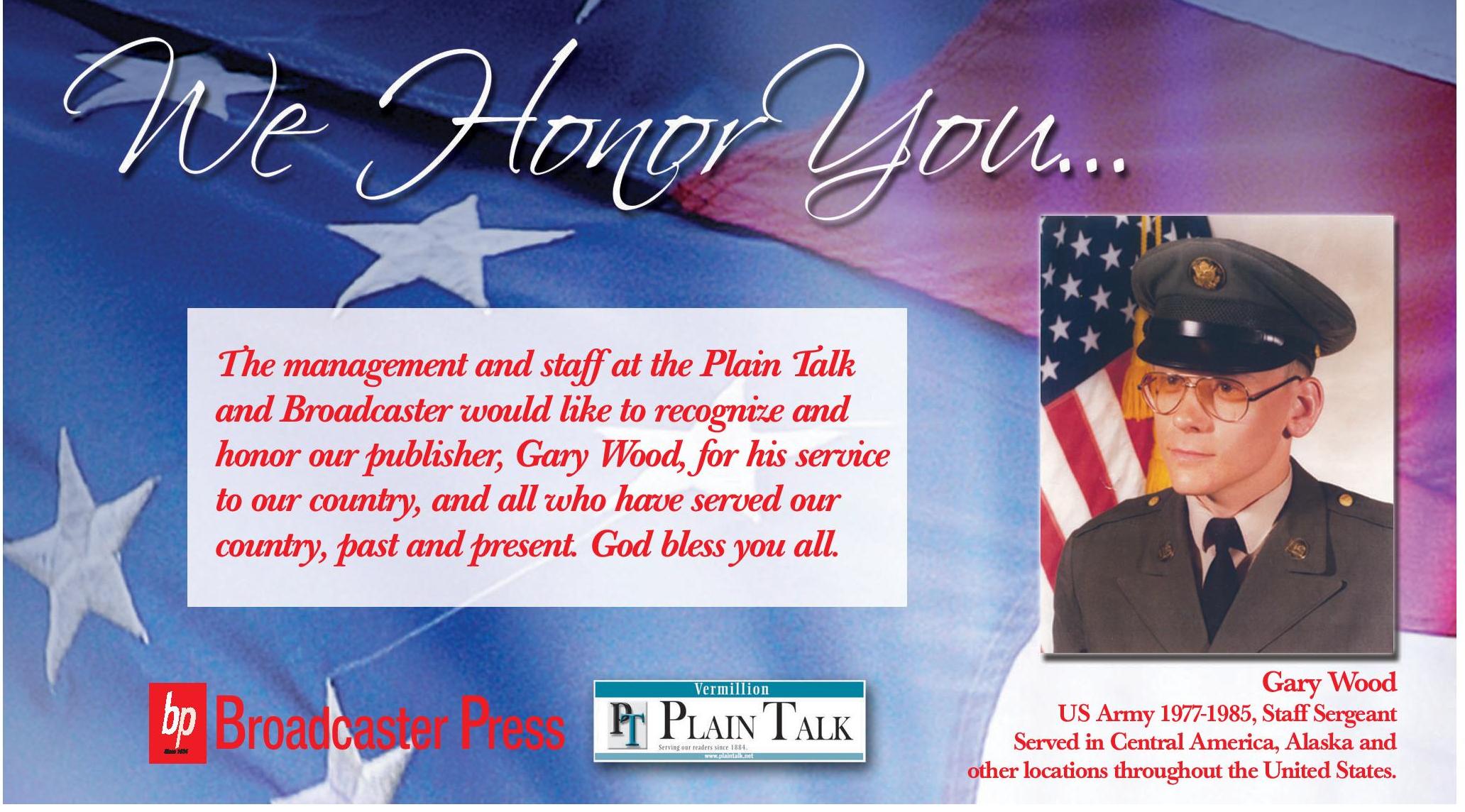

The management and staff at the Plain T

alk

and Broadcaster would like to recognize and

honor our publisher, Gary Wood, for his service

to our country, and all who have served our

country, past and present. God bless you all.

Broadcaster Press

Gary Wood

US Army 1977-1985, Staff Sergeant

Served in Central America, Alaska and

other locations throughout the United States.

Previous Page

Previous Page